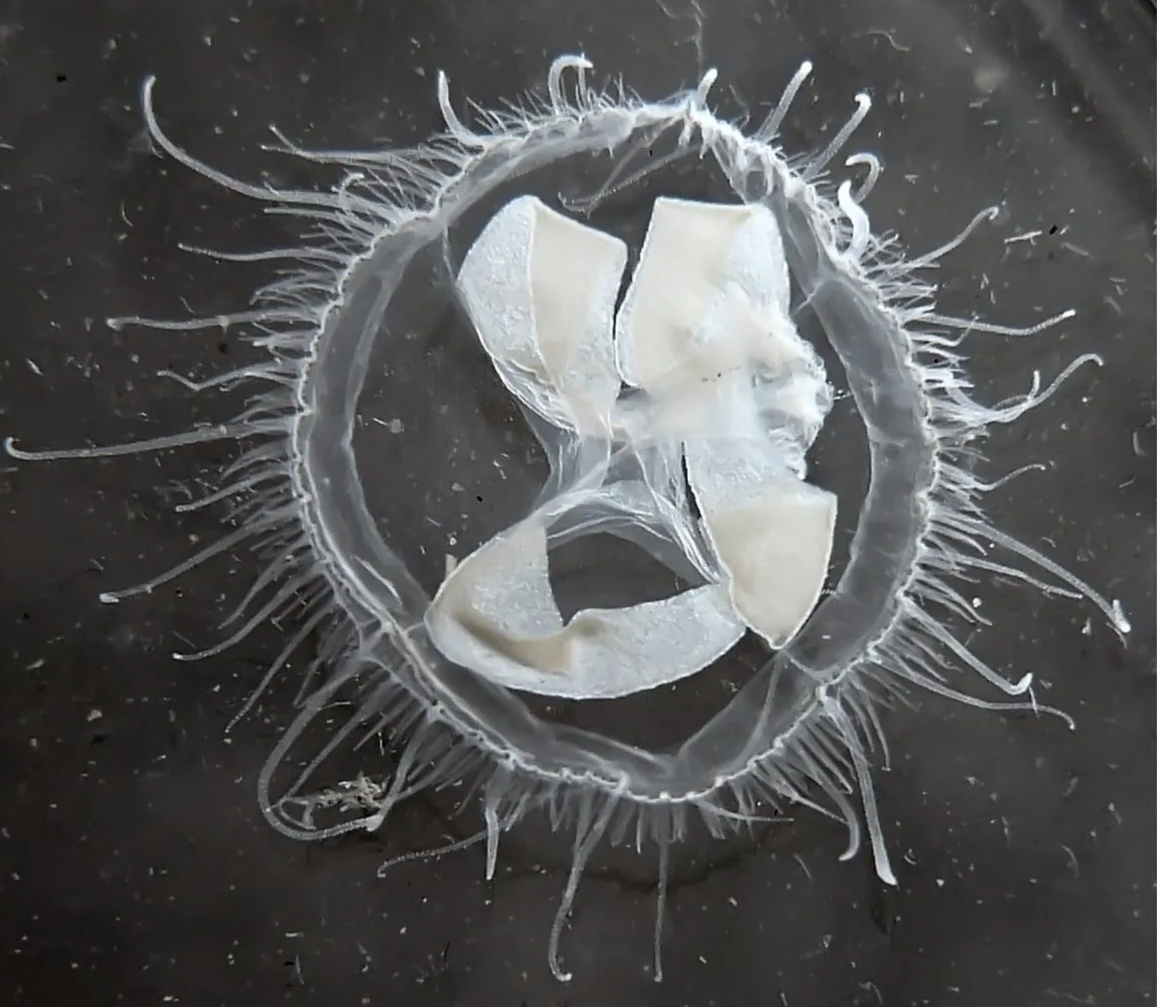

Freshwater jellyfish, Craspedacusta sowerbii: Thoto by Kai squires via Atlas of Living Australia. Licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

By Brendan Ross

If you are a regular beachgoer, you might expect to see jellyfish washed up after a strong onshore wind, but would you expect to find them living in our local creeks?

We recently got a surprise when a genetic survey of life in Enoggera and Fish Creeks, led by The Gap Sustainability Initiative and Save Our Waterways Now (SOWN), revealed something surprising: evidence of freshwater jellyfish.

As part of our 2024 environmental DNA (eDNA) survey, water samples were collected from seven locations in The Gap. These samples were later analysed, and among the hundreds of DNA fragments detected in the creeks, one stood out as the squishiest of all finds: the freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbii).

So how did they get here?

Should we be worried?

A Stranger Among Us

These tiny creatures are no ordinary jelly. Originally from the Yangtze River in China, this species has now made its way into freshwater lakes, reservoirs, and creeks all over the world, inhabiting every continent except Antarctica.

In our recent survey, these jellies were detected at five different locations, including Yoorala St, Riaweena St, and Taylor Range sections of Enoggera Creek, as well as Walton Bridge and Glenala St reaches of Fish Creek.

One Townsville website suggests that they were found in Enoggera Reservoir as far back as 1964.

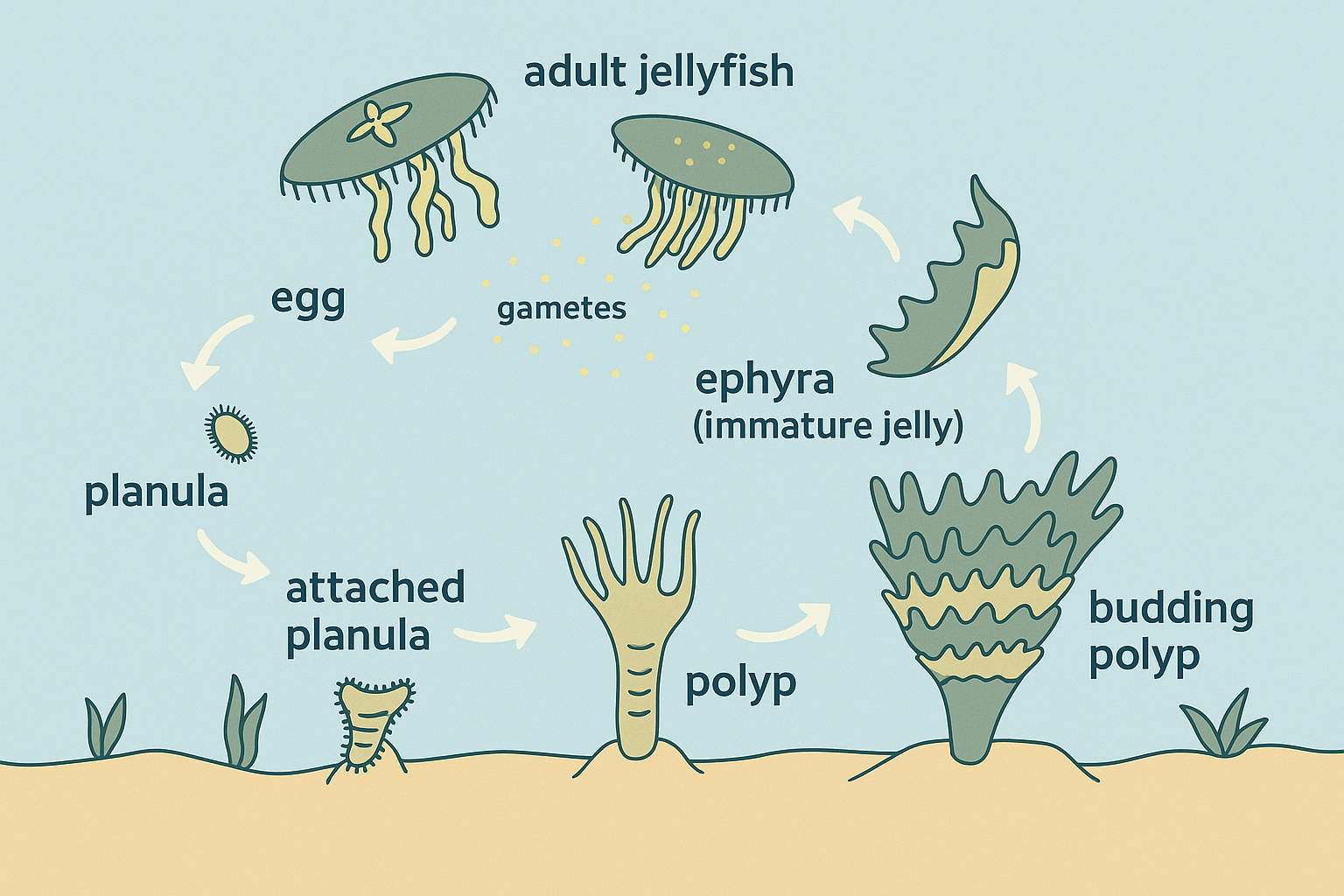

Life in Two Modes

A freshwater jelly’s life is mostly spent in an invisible, bottom-dwelling phase called a polyp. In this form, it clings quietly to submerged logs, rocks, or even aquatic plants, feeding on microscopic plankton.

Then, under just the right conditions, the polyps “bud off” dozens of tiny, free-swimming medusae, the classic jellyfish shape we recognise.

This video, from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand, shows the bell-shaped adults. They are typically no bigger than a 10-cent coin, and nearly transparent, making them notoriously difficult to see in the wild. Each night they rise toward the surface, pulsing as they hunt for microscopic prey in the water.

In our waterway, these jellyfish could go unnoticed for years, only suddenly revealing themselves through either chance sightings or, in this case, DNA left behind in the water.

Lifecycle of the Freshwater Jellyfish: Image adapted from Smithsonian Ocean Portal.

How did they get there?

The answer lies in their eggs and tiny polyps, which biologist Tim Low says can hitchhike a ride with introduced aquarium plants and fish. Other scientists also say boats, fishing equipment, and even the feet of waterbirds serve as jellyfish transports.

Because jellyfish polyps can survive for years in a dormant state, waiting for the right environmental cue to activate, it’s possible they waited many years, biding their time until conditions were right.

Will they sting?

While freshwater jellyfish do have stinging cells (like all jellyfish), their sting is so weak it can’t pierce human skin. Most people can touch them without feeling a thing. These jellyfish use their microscopic stingers to catch tiny prey like zooplankton, not to defend themselves. So if you’re paddling in the creek or reservoir, there’s no need to worry about these particular creatures.

Impact on the creeks

For now, there’s no evidence that freshwater jellyfish pose a threat. They have been present in freshwater systems across Australia for decades and are considered non-invasive, meaning they doesn’t appear to spread aggressively or outcompete other species.

However, their role in our local ecosystem isn’t completely understood either. What’s clear is that while they are not currently considered a threat to native biodiversity, continued monitoring is important. As with any introduced species, their presence reminds us how interconnected and dynamic our local ecology is, often in ways we don’t fully expect.

Craspedacusta sowerbii — freshwater jellyfish Photo by OpenCage, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons.

What You Can Do

You probably won’t see a freshwater jellyfish with your naked eye. They’re tiny, elusive, and more likely to appear only briefly during the warmer months.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t help protect the waterways to enable a range of other native wildlife to flourish.

That means keeping pollutants out of our creeks – think garden chemicals, detergents, or pet waste. And by planting native vegetation along creek banks, you can support everything from fish to frogs to platypus.

Join the Next Creek Survey

By joining our monthly Creek Surveys, you can help us to continue to build a clearer picture of what’s living in these waters – native or not.

Join the Next Creek Survey:

Location: Fursman Crossing Park, The Gap

When: Every 3rd Sunday of the Month from 8.30 to 10.30am (weather permitting and make sure you check our events calendar)